Integrated Marketing

I gathered research, developed a strategic plan and then, with a seasoned team, executed an integrated marketing campaign that filled the schedule of a new concierge medical practice in short order. We wrote, directed and produced an original 30-second broadcast ad and placed the spots thoughtfully, reaching health decision-makers, who watch television, an average of 8 times in 13 weeks. Our digital elements, geo-targeted paid search, delivered 1.2 million+ views in 90 days. A Sunday newspaper profile reached 90% of affluent, college-grad homeowners, a target demographic. And fresh video clips, new web content, and stepped-up community engagement helped reinforce our key messages.

MEDICAL INDUSTRY

Pulling the plug on insurance helps Germantown doctor focus on patients

By Kevin McKenzie of The Commercial Appeal

Posted: Oct. 31, 2015

Dr. Heather Pearson Chauhan said she was seeing about 34 patients on most days and spending time checking the right boxes to meet insurance mandates when she decided she'd had enough.

"I thought to myself, I'm 40 and I'm probably going to practice medicine for another 30 years," said Chauhan, a Memphis gynecologist and obstetrician who worked at the Ruch Clinic for a decade.

"And I thought, I'm unwilling to do it this way for another 30 years because this isn't focusing on the reasons that I became a physician, and this isn't focusing on the patient as the center of everything."

The chief executive of the Tennessee Medical Association, Russ Miller, described the "turbulence" for physicians and the health care industry that may lead to soul-searching about the direction of the medical profession.

Health reforms triggered by the federal Affordable Care Act aren't the only causes.

"We're changing payment models with TennCare innovation grants, wholesale sellouts of physician practices to hospitals, small groups merging with larger groups, specialties blending to become multi-specialty groups," Miller said during a visit to The Commercial Appeal last week.

"Everybody's trying to find a safe haven, a little bit of cover during all this turbulence," he said.

The state medical association's president, Dr. John Hale, a Union City primary care physician with Baptist Medical Group, said transitions like the Affordable Care Act and electronic medical records create a certain level of frustration.

"Some people roll with it, some people, depending on their circumstances, say 'I'm going to get rid of it, I'm going to do something different,' " Hales said. "Anytime you have fundamental change like that, then most of them go on and keep working because they are called to do it."

One year ago on Nov. 17, Chauhan opened her own answer to putting the focus back on the patient and on the time that physicians should take to spend with them, she said.

Her answer is called Exceed Hormone Specialists, a practice that doesn't accept health insurance. She found the more-intimate setting she was looking for in a residential-style office building in Germantown at 7512 Second.

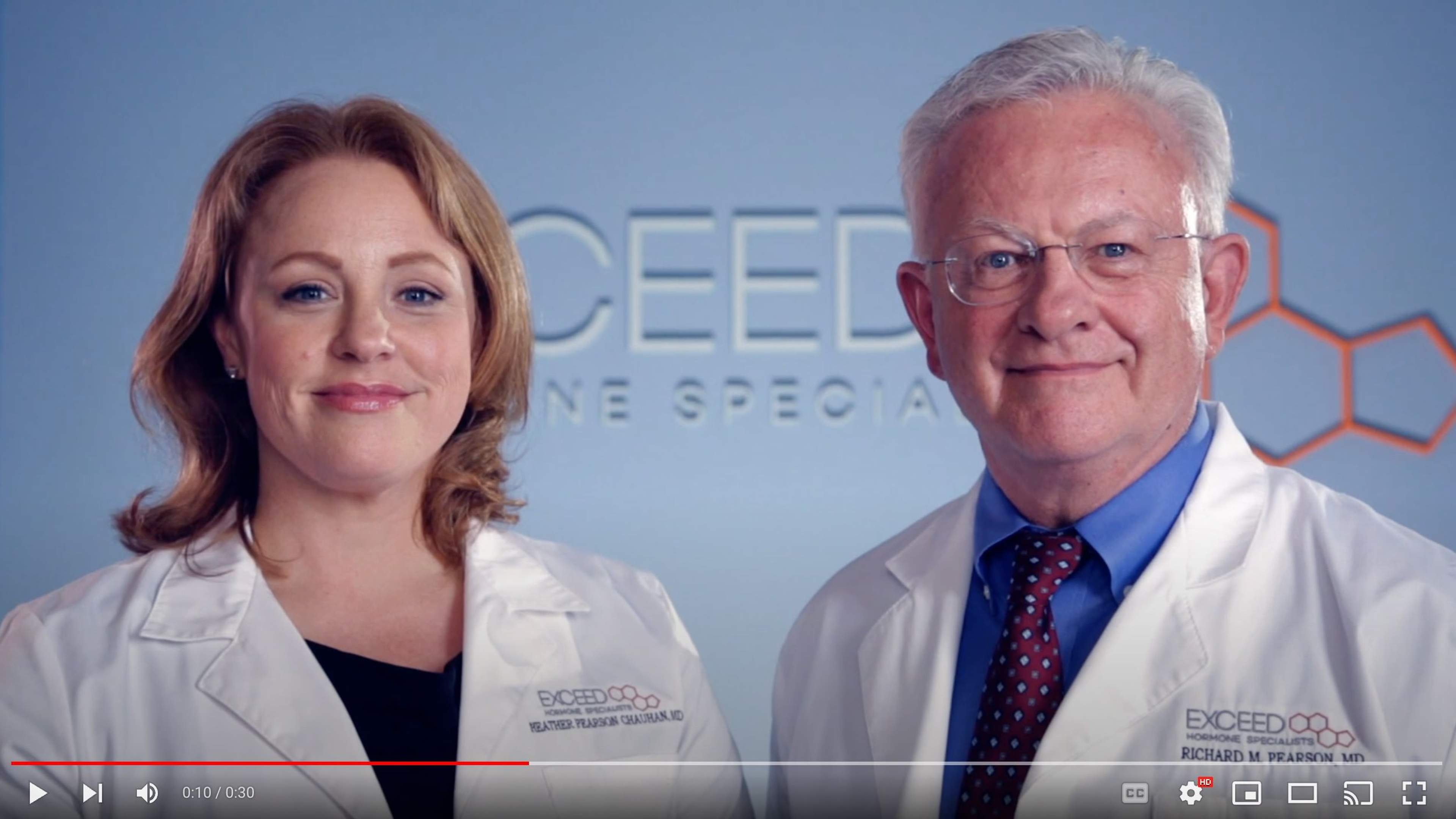

There, she and a partner who is also her father, urologist Dr. Richard Pearson, aren't driven by what she said frustrated her most in a traditional practice driven by patient volume and insurance documentation.

"Direct pay" or "concierge" practices are common labels used for those that have cut the cord with insurance. While producing revenue, insurance claims are also a cost.

"If I have to employ two to three people to work on claims and insurance, then that's three more salaries I have to pay, which is lots less time I get to spend with patients because I have to bring more money in to keep my doors open, and we go right back to the system I'm trying to come out of," she said.

At Exceed, prescriptions may involve diet and exercise, as well as hormone replacements. "Bioidentical compounds," chemically identical to natural ones and that insurance companies won't pay for, are prescribed, she said. Hormones including testosterone, which both men and women may require, are delivered by pellets implanted under the skin. In men, they last five or six months, she said.

The time spent with patients also allows for a more in-depth and broader search for the causes of health issues ranging from tiredness to sexual dysfunction, Chauhan said. She encourages "baby steps" that concentrate on changing one thing at a time.

"If you just treat the disease process and don't treat the environment in which the person is dealing with the disease process, then you're not really helping them," she said.

That's a focus that "wellness coaches" are more commonly adding to internal medicine and family physician offices in the western United States, she said.

"What those physicians believe, and I'm sure this will grow east, is that if you can have a practice that provides not just medical care, but lifestyle management, all of those things are integrated," she said.

In Memphis, the Church Health Center provides a similar model.

After a free, 15-minute discussion of whether to proceed, costs at Exceed include $300 for the initial consultation and run about $100 a month for a year's worth of hormone management, Chauhan said. Patients sent for lab work may have the labs bill their insurance, and Exceed provides patients with codes if patients want to file for reimbursement.

Glimpses of her father's rapport with patients during her summertime filing and hole-punching at his office inspired her goal to establish the same relationship with her patients, said Chauhan. She's a Princeton University history major who went to medical school in Memphis at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

Pearson, 71, a founder of the Conrad|Pearson Clinic, doesn't take a salary as her partner, said Chauhan. Her mother, Freida, isn't receiving a salary as practice administrator. A practice coordinator and a nursing position shared by two workers round out the staff.

A mother of two, her husband, Dr. Ravi Chauhan, is a urologist with Conrad|Pearson.

Chauhan said the entrepreneurial spirit of her younger brother, Taylor Pearson, also inspired her. At 26, he has published his first book: "The End of Jobs: Money, Meaning and Freedom Without the 9-to-5."

For the practice, the name Exceed reflects her main goal, to exceed people's expectations of what a doctor visit in 2015 is going to be., Chauhan said.

"I want their experience here not to be what they expect it to be," she said. "I want them to feel that more attention and more time and more listening was given to them than they have seen in practices before."